Exploring Quake 3's Fast Inverse Square Root

A brief explanation and exploration of the iconic quake 3 fast inverse square root.

Introduction

The following code, which may have been written by John Carmack, was found when the Quake 3 source code was open-sourced:

float InvSqrt(float x) {

float xhalf = 0.5f * x;

int i = *(int*)&x; // get bits for floating value

i = 0x5f3759df - (i>>1); // gives initial guess y0

x = *(float*)&i; // converts bits back to float

x = x*(1.5f-xhalf*x*x); // Newton step, repeating it increases accuracy

return x;

}

Whilst most code looks complicated, this one even baffled most but the best software developers, whilst this wasn't originally created by John Carmack and was shown as early as in the late 80s, developers around the world struggled to understand how this piece of code functioned and more importantly why it was used.

In the early 90s, unlike our modern-day processors, video games were a relatively new concept and suffered heavily from hardware constraints. Now our modern-day processors are; faster, more optimized, and better balanced with relatively equal speeds for all instruction sets. However, in the early days of computing, this was not the case.

Due to this, developers had to be creative in order to find unique ways to bypass these hardware restrictions, hence the inverse square root "hack" was born.

Whilst with most games, heavy optimization is possible, it is typically not done. Heavily optimizing a game, or even a function may not be cost-effective or worth it in performance vs development time tradeoff. However, in the case of Quake 3, it was beneficial. In video game graphics, specifically 3D engines both; Pathing, lighting & reflection all heavily utilize vector normalization techniques. As these normalization functions may run hundreds if not thousands of times per frame in a game. As lighting conditions update and enemy AIs recalculate their paths, this simple function can become incredibly computationally intensive quite quickly.

Whilst this operation may seem simple, especially for an integer, at the time, calculating the reciprocal of a floating-point integer was incredibly computationally intensive and this fast root bypassed this step. As a result, this floating-point hack managed to shave off the time required to perform this calculation by opting to use an incredibly accurate approximation instead, treating the floating-point as an integer in most places.

History

The origin of the source code for the video game Quake III was officially released in 2006 during the annual QuakeCon convention, which is 7 years after the game's release. QuakeCon is a yearly gaming event held by ZeniMax Media to introduce and celebrate id Software games and other studios. The author of the code is suggested to be Teje Mathisen, who is an x86 assembly language programmer that helped the company id Software with Quake optimization within their video games. He was able to utilize some code which he had written during the late 1990s which was used for 3D computer graphics, which can be seen in id Software’s first-person shooter game in 1999, Quake III Arena. This code was crucial to the creation of the Fast inverse square root function and is thought to have been sourced from the SGI Indigo computer work station, run by Gary Taroll in the 1990s. Although, after years of investigating, the original author of the Fast Inverse Square Root function was found to be Greg Walsh. He has had many monumental impacts upon the computing world and has helped develop the technologies we have today.

The history of how the magic number 0x5f3759df, which is used in the Fast Inverse Square root function, is not precisely known by researchers but has been developed and improved by mathematicians over the years. Chris Lomont was able to improve the number by minimizing the approximation error when choosing the magic number over a given range.

How Does The Code Work?

The FastInvSqrt was created to tackle a reappearing problem in computer graphics, needing to compute a normalized vector. If you have a vector, to normalize it, you compute: $\frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}}$. For the initial good guess, we want to know what $\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}$ or $x^{-\frac{1}{2}}$ is equal to. We begin by dividing our input floating-point number by two and storing it in the variable “xhalf”.

The line of code i = 0x5f3759df - (i>>1) computes this initial guess $y_0$, roughly by multiplying the exponent for $x$ by $-\frac{1}{2}$, and then picking bits to minimize error. i>>1 is the shift right operator in the programming language C, which shifts the bits of an integer right in one place, dropping the least significant bit, effectively dividing by $2$. This divides the number in half, but also has the unintended consequence of adding a random bit onto the "left" of the exponent that should have been part of the other half.

0x5f3759df is a hexadecimal number, just a constant. In decimal form, it is 1,597,463,007. When we take our new $y_0$ value and subtract it from the hexadecimal constant above (0x5f3759df - y0), the bits line up in such a way that the exponent half of $y$ goes from positive to negative. The "extra bit" that was pushed into the exponent gets put back into the other half, and the other half pushes over to make room for it.

We take the “$x$” variable and re-interpret that integer as a floating point number. Now it is finally time to compute one iteration of Newton's method of approximation to make our initial guess even better. Newton's root finding method can be shown as:

$y_{n+1} = y_n - \frac{f(y_n)}{f'(y_n)}$. For the $f(y)$ given this can be simplified to:

$y_{n+1} = \frac{1}{2}y_n(3-xy^2_n)$. Which corresponds to our line:

[x = x * (1.5f - xhalfxx)]. Where x is the initial guess. End result is a number really close to the real answer, we get a rough approximation for $ x^{-\frac{1}{2}} $ - the inverse square root.

Testing Quake's Fast Inverse Square Root

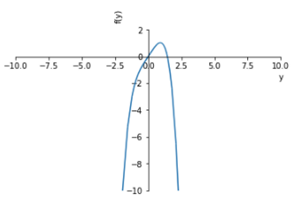

Most of the lines of code in the function are assignments/arithmetic which cannot be graphed aside from the final line as mentioned in the section *‘How does the code work’*. The image above displays the generated graph for the final line of the function, one iteration of Newton’s method where ‘$y$’ symbolizes the first estimate and ‘$f(y)$’ symbolizes the final returned estimate.

Testing Quake's Fast Inverse Square Root

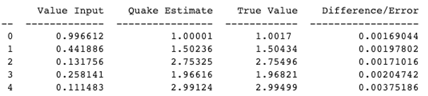

To test the accuracy of Quake’s fast inverse square root, the code was first translated into Python using NumPy. Then a new function, called true value, was coded to calculate the true inverse square root value. A random float number was generated and its inverse square root was computed using both the Quake function and the true value function. Both values as well as the difference between the two was stored in an array. This was done inside a loop to generate results for five random float numbers.

def Q_rsqrt(number):

threehalfs = 1.5

x2 = number * 0.5

y = np.float32(number)

i = np.int32(0x5f3759df) - np.int32(i >> 1)

y = i.view(np.float32)

y = y * (threehalfs - (x2 * y * y))

return float(y)

def true_value(number):

return number**(-1/2)

table = []

for i in range(1,6):

x = random.random()

test_results = [x, Q_rsqrt(x), true_value(x), true_value(x)-Q_rsqrt(x)]

table.append(test_results)

df = pd.DataFrame(data=table)

print(tabulate(df, headers=['Value Input', 'Quake Estimate', 'True Value', 'Difference/Errors']))

As you can see, the Quake estimate and the true value for the five random numbers have a difference of less than $1e-2 (0.01)$, making Quake's function accurate to 2dp.

Conclusion

I personally found this topic very interesting, great programmers writing even greater code. Even though this wasn't made by solely one person, but instead several through open-source work & collaboration. It can show how even a simple problem can be tackled and optimized to insane levels for the sake of efficiency or convince for programmers. Whilst normal computers nowadays have optimized instruction sets and clock speeds making this performance trick redundant. Many other programmers still continue to follow these same trends of efficiency even to this day, writing innovative and frankly insanely optimized code, that many of us wouldn't know how to read, let alone code.